« Article Number Two PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Senufu Helmet Masks

Article excerpt from Senufu Sculpture from West Africa by Robert Goldwater

The Museum of Primitive Art, New York, 1964Senufu Helmet Masks

While the best of the Senufu face masks are distinguished by an almost miniature-like conception, quite the opposite is true of their helmet masks. Almost all of the several kinds are characterized by a broken, bristling silhouette made of an assortment of jaws, teeth, ears and horns put together on a large scale and executed with vigor. [see image 51] senufu helmet masks

This is not to say, in the language of older commentators, that they are “crude,” meaning that they do not reach an acceptable level of craftsmanship (and naturalism). 40 Quite the opposite is the case. Composing so iconographically complicated and visually intricate a program from a single block of wood requires sculptural imagination and technical planning, all carried out with attention to detail and surface. But it is immediately evident that whatever ideas their parts may embody, these masks are meant to impress, and to terrify. And this is, in fact, their functional role.

51 Helmet mask (“Firespitter”). Central region, Korhogo district (S). Wood, 33 1/2″ high. Collection Mrs. Frans M. Olbrechts, Wezembeek, Belgium.

52 Helmet mask (“Firespitter”). Central region, Korhogo district (S). Wood, 36″ long. Musee de l’Homme, Paris X50-368

The ceremonial purpose and the visual effect are therefore very different from those of the delicate face mask, and this range and variety is one of characteristics of Senufu sculpture. Yet in the manner of their conception there is a certain similarity, for both face and helmet masks consist of a gathering together of separate, and naturalistically incongruous elements. In the face mask there is a juxtaposition of human and “abstract” components; while here, although each of the parts is drawn directly from nature, they are not to be found together in the natural world. The most common of the animal masks, whose prominent features are its single muzzle and long horns (the type that has become to be known as “firespitter”) [see image 52], can include iconographic details taken from the buffalo, the wart hog, the crocodile and the antelope [see image 53], in its larger parts, plus small representations of a chameleon and a bird, even sometimes a snake. [see image 54] It would seem correct to say that this sort of additive compositional imagination is more characteristics of Senufu art than of other African styles.

It serves, at any rate, to emphasize an important fact about these masks: what they depict (i.e., the sources they stem from in nature), is very different than what they finally represent (i.e., the ideas they embody in ceremonial use). 41 It is perhaps quite clear that this must be true of the imaginatively constructed creature of the usual fire-spitter, but one must remember that it applies as well to the simpler forms without horns that are derived from the baboon or from the hyena. The intention of all of them is the same: ceremonially, these are demons rather than animals, and, while they are in us at least, they fuse with the demon, or his spirit with them, and temporarily become his embodiment.

53 Helmet mask (“Firespitter”). Central region, [S]. Wood, 31 1/2″ long. Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leden 3319-6

54 Helmet mask (“Firespitter”). Central region, [S]. Wood, 35 5/8″ long. MPA 57.248

In their added details the iconographic allusion of all these masks carries further, so as to connect with the recurrent body of Senufu mythology. Crowning the helmet portion of most of the horned masks, whether of the single or double-muzzled variety, and of many of the hornless ones as well, are one or more small representations, whose size is of no measure to their importance: there is the familiar hornbill, symbol of fertility, and the associated masculine symbol of the python, whose form may be abstracted to a sinuous line, therein in the chameleon, which by its “hesitant and cautionary walk recalls the undifferentiated mud of the primordial universe”; and finally there is the little cup (often supported by hornbill and chameleon) [see image 52], which “is filled with a special substance supposed to guarantee the efficacy of the ritual”. 42 It is this cup, or perhaps the material that fills it, which is called wa, [see image 57] that gives the masks that carry it their name of waniougo. The waniougo, [see image 11] Holas informs us, is a special form of this type of mask whose more general name, applied as well to versions without the cup, is kponiougo, [see image 10] meaning “head” or “countenance” of the lô. He assigns to the mask a mythological and practical role similar to that of the sacred statues; “[it serves as] a connecting link between humanity and the amorphous universe of the ancestors on the one hand, and between humanity and its protecting gods on the other” 43 It plays an essential role in agricultural, initiatory and funeral ceremonies.

57 Double helmet mask (“Firespitter”) with costume. Central region, Nebunyonkaa village, Kiembara fraction [F: collected by Dr. Albert Maesen in 1939]. Wood, native cotton, paint, 29″ long. Etnografisch Museum, Antwerp AE.55.30.23

Two older descriptions of these animal masks assign them a somewhat different role. Prouteaux in 1914, and Maesen in 1938, concluded that the chief function of the masks is the driving away of the soul eaters. 44 They connect them primarily with secret societies (which vary from place to place) other than the ló, and agree that though these or very similar masks also appear at funeral ceremonies of members of the society they are not in the first instance funerary masks. The purpose of the mask is always to inspire fear; it has such great power that even the initiates must observe certain taboos in handling it; touching its costume during its appearance may be dangerous even for the initiated, while its sight for a non-initiate, and particularly for any women, will cause sickness and possibly death. 45

60 Dancer with helmet mask in initiation ceremony, 1954. Central region, Korhogo district, Sinématiali village, Naffara fraction.

Prouteaux was present at the dance of one of these horned masks, which he calls gbon, and describes it in detail. The dancer, who was required to be nude under his ritual costume was hidden by a large mantle of raffia braids which came down to his knees, and his legs were covered by trousers of a rough material. The gbon appeared at night after the population had been gathered by the drumming of young boys, who also sang gaily as they waiting for his entrance. The mask, accompanied by drums, trumpets and chanting, and the ore piercing sound of flail, held a leather whip as he walked and turned, sometimes on tiptoe, and sometimes on his knees. “At his approach everyone kneeled and bent down, their eyes fixed on the fringes of costume spread out by his pirouettes, and whose touch they had to avoid . . . ; [but the sorcerers] hypnotized by the devilish music of the adepts, and by the presences of the spirit in the village, cannot hold still, and are driven out.” 46 The gbon is said to have superhuman powers; it can seat itself unharmed on a fire of glowing coal, which will then be put out; with a single bound it can climb into a tree or on top of a house; it can throw sparks through the straw roof of a sorcerer’s hut without setting it on fire.

61 Helmet mask with costume. Central region [S]. Wood, copper, fibre, 15 3/4″ long. Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden 3432-2.

But the most curious practice of the gbon, says Prouteaux, is firespitting. From time to time, the gbon “lets fall down his costume two fist-fulls of sparks and tiny glowing coals which rapidly die out upon touching the ground. These jets of flame are very skillfully executed, and male a great impression on the audience. Certainly it is paradoxical to have fire fall across a curtain of hemp without anything catching fire. And the supply of embers is large enough so that half an hour after [the mask’s] entrance it has not been used up.” 47

Maesen describes the mask’s appearance in the evening, as prepared for by a ritual that included its painting with red and white earth colors both spread and spotted, the attachment of small goat horns as magic containers, and the assertion of bird feathers.” 48 Because the mask must be put into a good mood for the pursuit of the soul-eaters, it is offered sacrifices both before and after the chase. In hos observation, the masks do not execute a dance but rather simply walk and run. At a certain point they disappear into the bush, and thence give forth roaring cries as the sign of victory at having surprised a soul-eater. He also witnessed the firespitting performance of the demon “who blows sparks through the muzzle of the mask and, ends his performance dancing barefooted upon a pile of burning logs until they are extinguished.” “Before setting out in the open savannah, at night, the masks ran through the outskirts of the village. They were part of a small band of society members roaring incantations and drumming. From time to time the mask wearer shouted formulas in a high-pitched tone, and proceed to blow out a small blast of glowing sparks and little flames. This was produced by means of grass properly cut in tiny pieces and smeared with a sort of resin also used on torches. The mixture was ignited from inside the jaws of the mask by the bearer blowing upon a small but heavily ash coated piece of smouldering wood from the narrow core of a tree”. 49

62 Helmet mask. Central region? [S]. Wood, traces of paint, 10″ long. Seattle Art Museum, Eugene Fuller Memorial Collection Af16.4

Maesen notes that although the function of the helmet mask is invariable its name alters according to the local organization to which it belongs. As Prouteaux uses gbon to refer to these masks generally, so Maesen (as well as Himmelheber) employs korubla as a generic appellation. Both Holas and Bochet, [see image 12] however, indicate that korubla is a much more specific name designating a hornless mask without the cup, or wa, on its forehead, [see image 60] and depicting a baboon.50 This is a funerary mask, much more closely connected with the lô society and its initiation ceremonies. It is worn with a cynocephalic mane, and the dancer carries a double membrane drum on his chest; it is fitted out with feathers, and with bundles of porcupine quills and the dried bodies of hedgehogs. There are two types of korubla masks. In one, the animal alone is represented, so that despite the convention of the joined teeth, the naturalistic source is quite evident (Leiden and Seattle). [see image 61] [and 62] In the other (British Museum), by a different treatment of eyebrows and eyeball, and by the addition of a projection below the nose which is referred to as a mouth (as distinct from the jaws) a human face has, as it were, been laid over the animal muzzle. [see image 55] The fusion is found in other korubla examples which are all without horns although they may carry the chameleon or hornbill; it is also typical of the horned masks, whether or not they have the magic cup. [see image 56]

Given their primary demonological intention, and the mixture of sources that has already been noted, and inquiry into the specific animal from which each of these masks derives may not seem pertinent, On the one hand the artist has had his rendering severely limited by tradition; on the other hand a good deal of imagination has gone into the creation of that tradition; on both scores exact transcription suffers. But this morphological problem is linked with that of geographical distribution and provenance.

56 56a Helmut mask. Cebtral region, Korhogo district, Faidonga village. [F: collected by Mr. F.-H. Lem]. Wood, 17 1/2″ long. Collection of Madame Helena Rubinstein, Paris.

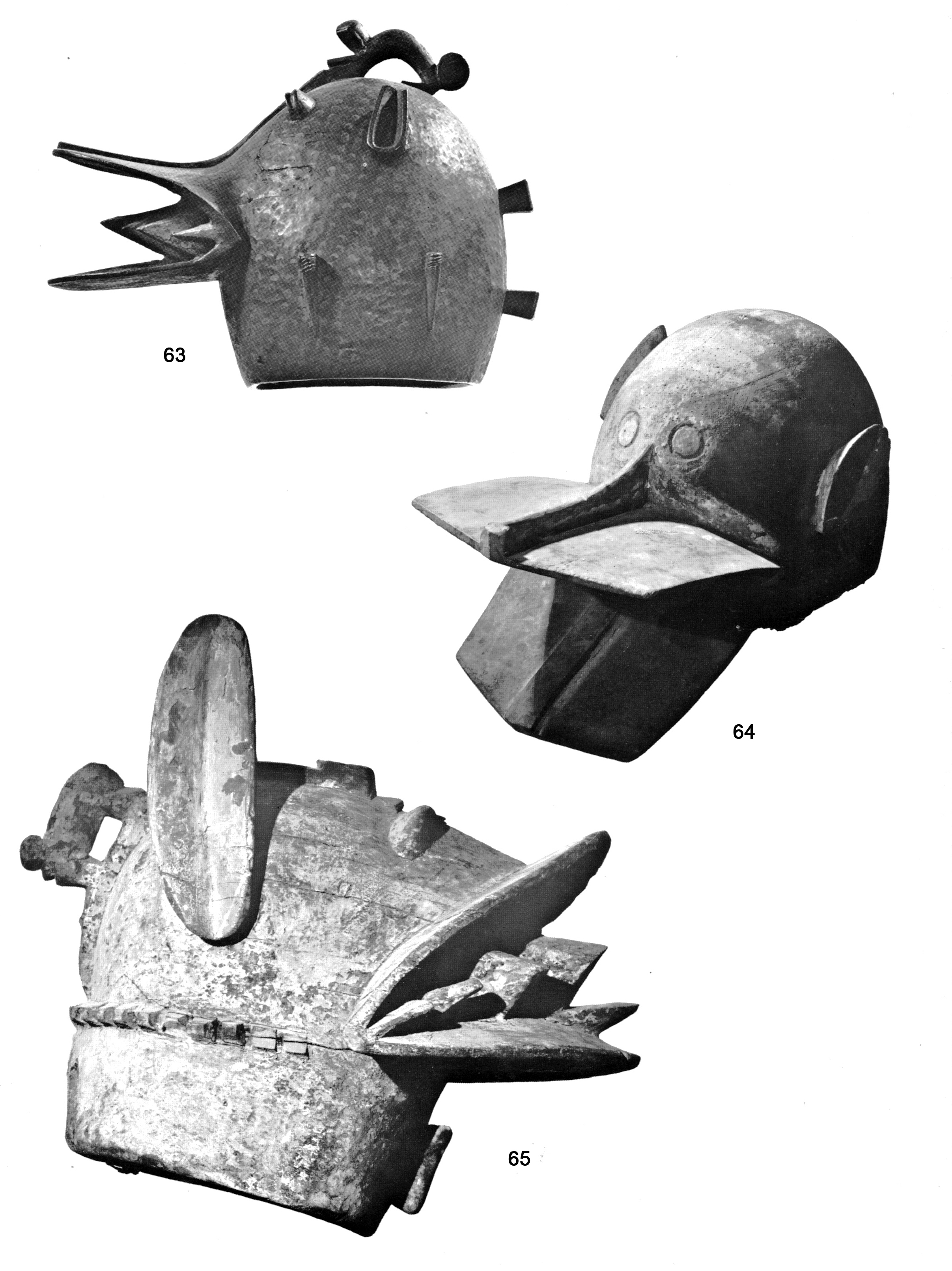

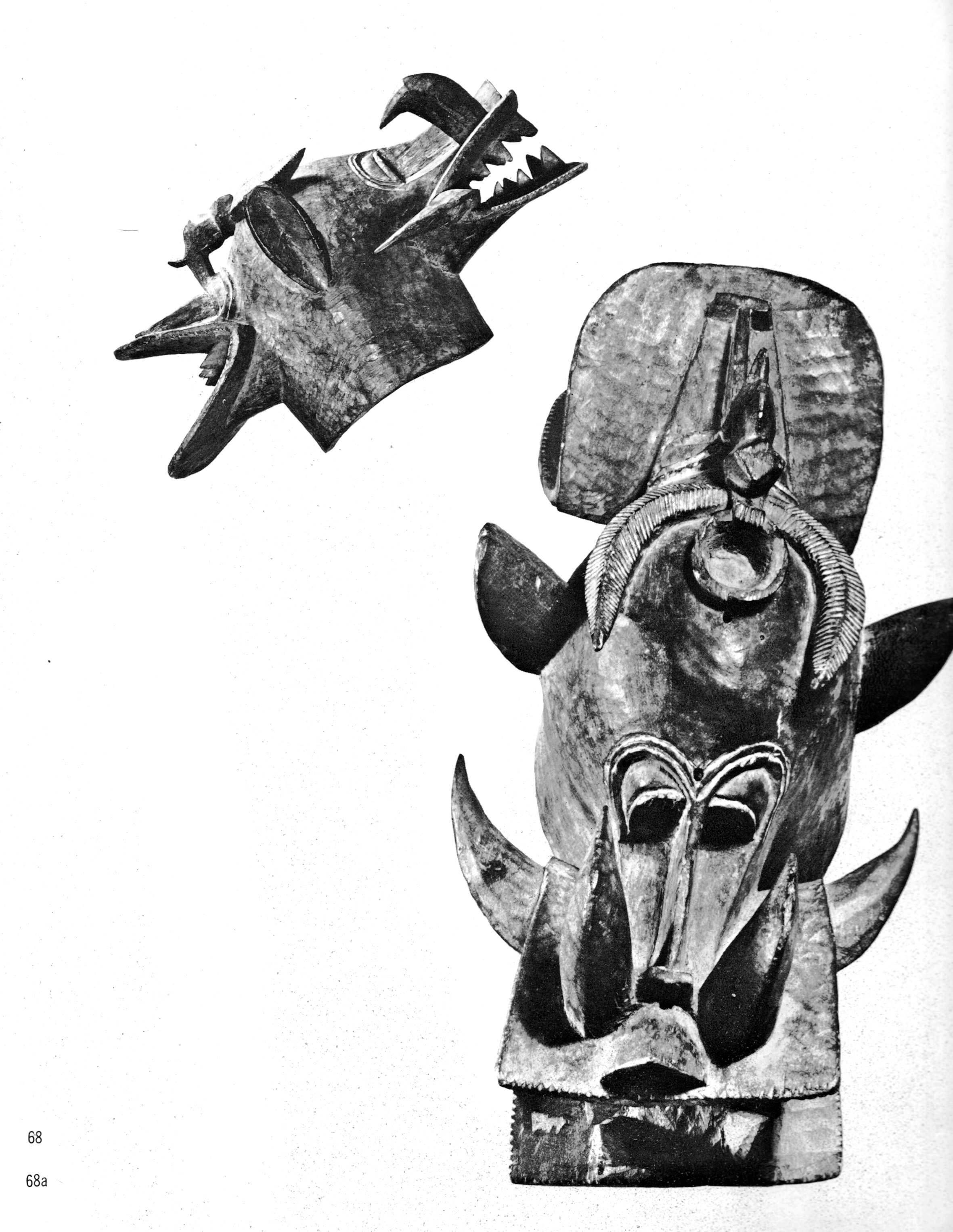

The characteristic “firespitter,” documented by the Prouteaux photographs (1914), the Bochet drawing, and the “dated” examples in Paris, Antwerp and the collection of Mrs. Frans Olbrechts—the type that occurs most frequently—comes from the central region. [see image 57] Apart from the features on the crown, which may include either or both antelope and rams horns, these masks have a double set of tusks, one out of the nose and one out of the jaw, which suggests a warthog. This applies equally to single and double-faced, although where the nose is very narrow and the jaw very wide (Paris) there may also be a suggestion of the waterbuck. [see image 52] Maesen, who worked in the central region, refers to a boar mask with horns, and Lem, near Korhogo, collected a hornless mask with one set of tusks in the jaws which he describes as the “boar-man.” 51 Lem also found two “hyena” masks, one single, the other double, which have directly carved on them the small goat horns that are usually attached, in the Folona district in the north. 52 [see image 63] The considerable stylization of this type is in line with the tendency toward abstraction generally held to be characteristic of the more northern areas. Thus another, rarer type of bovine helmet mask (also first collected by Lem in the “thirties”) [see image 66]has on these grounds been attributed to the northern Senufu area. 53 Where then is one to place the provenance of the double mask in the Deskey collection, [see image 68] one of whose muzzles is of the typical central region type, while the other has the wide flap-jaw and withdrawn teeth found in the Folona examples? The association is one work of two apparently distinct tendencies once more suggests that mutual influences were more widespread that we have been wont to assume, and that one must not be overly rigid in associating a given style with a single region.

Kagba and Nassolo

63 Helmet Mask. Central region, Sikasso (Folona?) district, Siene village [F: collected by F.-H. Lem]. Wood, 22″ high. Collection Madame Helena Rubenstein, Paris.

64 Helmet mask. Wood, traces of paint, 18 1/8″ long. MPA 59.216,br />

65 Helmet. Wood, 15 1/2″ long. Collection Mr. Mrs. Samuel Rubin.

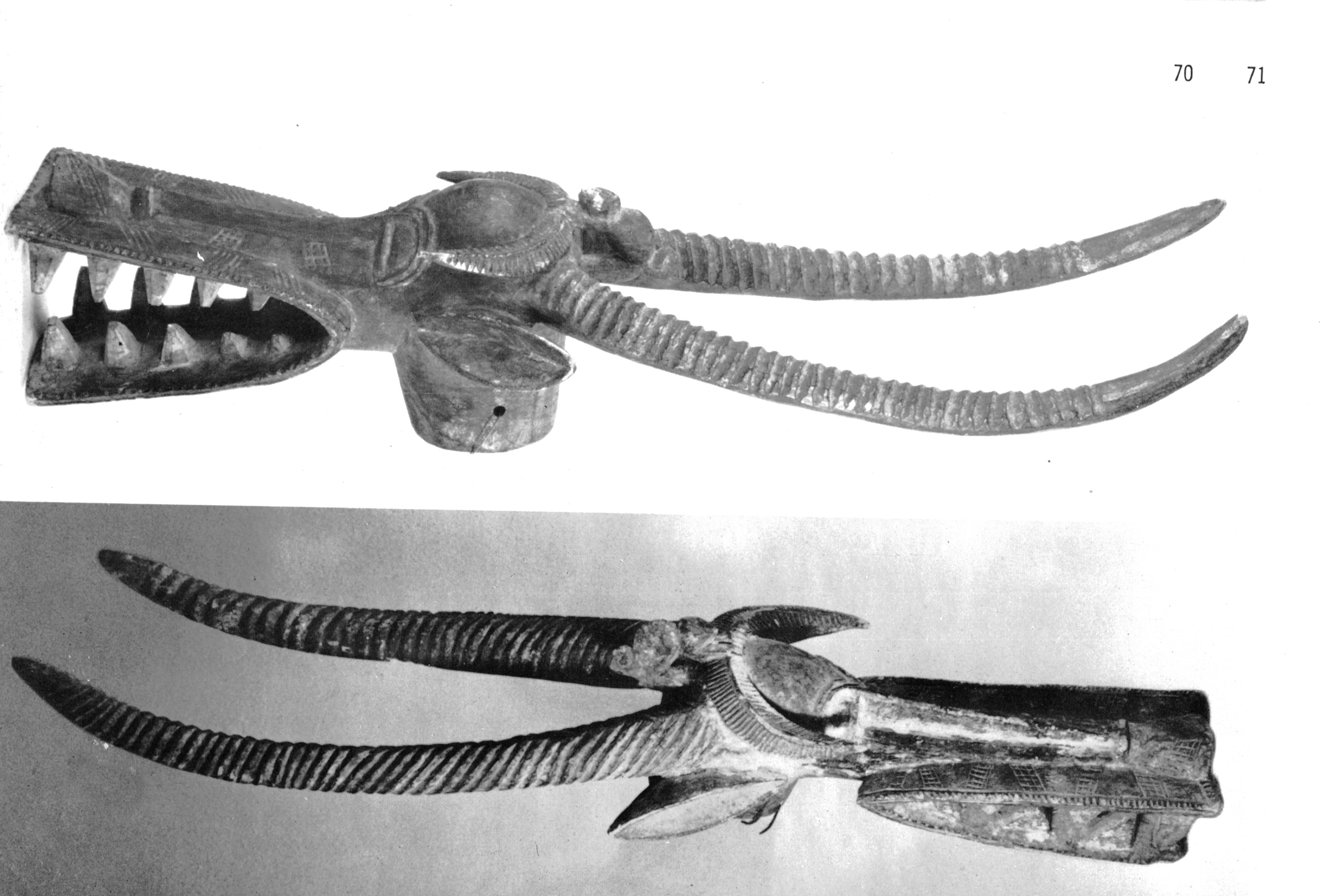

There is still another, reduced version of the animal mask. As it turns up in western collections divested of its attendant costume, with elegant proportions, carefully executed detail, and a headpiece apparently too small to be worn, [see image 70] it looks as if it might be a “nonfunctional” work of art. It is slim and drawn out, with winged antelope horns that sweep up and rams horns that bend down, a small chameleon on the forehead, and a long, thin snout that projects from a narrowed section of the face. [see image 71] But it clearly cannot be worn in the usual manner of the helmet mask. Here’s where a striking instance in which knowledge of context is indispensable of any understanding not only of a work’s intent and function, but also of it’s original visual effect.

What that was may best be grasped from the drawing by Bochet, [see image 13] which we reproduce. This shows the wooden mask as the small head of a much larger body, the whole known as kagba (house of the village). The wearer, naked beneath his covering, carries a large tent-like structure made of a liana framework on which has been stretched a surface of palm leaves painted with symbolic designs in white, black and ochre, or in blue and white.

66 Helmet mask. Northern region [A: cf. Elisofon Pl.109]. Wood, 27 1/2″ high. MPA 56.373

67 Headdress. Northern region? [F: collected by F.-H. Lem in Fenkolo village, Siskasso district]. Wood, metal repairs. 19 1/2″ high. Collection Madame Helena Rubinstein, Paris.

At one gable peak is the wooden, sculptured head, at the other a raffia tail. Only lô society initiates may view the kagba, which is its symbol; to others it brings death, so that when it is carried in funeral ceremonies people take refuge into their houses. Then, Father Knops tells us, “a sinister silence descends on the village, broken only by the regular, lugubrious droning of the rhomb . . . which produces a sound like the lowing of a bull . . . masked by a cloth stretched in a triangle, and armed with a whip, precede it while they produce a shrill whistling sound” 54

One of these masked attendants, dressed in a spotted costume that covers him completely, may be seen in a photograph taken at Sinematiali which shows what Holas has described as an improved form of the kagba, known as nossolo, a word literally transcribed as “buffalo-elephant,” i.e., a buffalo the size of an elephant. The nassolo is some ten feet long, to the six of the kagba; it is rounded rather than triangular in section; and its increased size requires it to be carried by two men. It, too, has a carved animal’s head at one end, and a noise-making apparatus manipulated on the interior. Bochet describes the nassolo as “a remarkable attempt to group together the largest possible number of symbolic elements in order to suggest the totality of the initiation

sequence and structure.” 55 This applies to the kagba as well, and it is noteworthy that these masks are confined to the Naffara faction of the Senufu, in the districts of Farkessédougou and Sinématiali, and that the Naffara add to the three usual stages of lo society initiations, a fourth higher level, which they call kagba. 56 Thus both mask and grade are a kind of summing up.

68 68a Double helmet mask (“Firespitter”). Central region? [S]. Wood, 25″ long. Collection of Donald Deskey courtesy of Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

Notes

40. The older view is exemplified in the comment by Delafosse, 1908-1909, p. 271, who, after referring to the “infantile state” of Senufu sculpture in general, continues, “C’est surtout dans la confection des masques religieuses que se révèl l’art indigène, et encore cet art, rustiqu dans l’exécution conventional dans l’invention, est-il tout à fait grossier.”

41. Maesen, 1940, pp. 389-390

42. Holas, 1962, pp. 15-15. In the Josef Muller collection, Solothurn, is a double mask very similar to that in The Museum of Primitive Art. See Bern, 1953, no. 93 and ill.

43. Holas, 1962, p. 14. Himmelheber, 1960, pp. 101, 103 assigns these masks to the lô society of the “farmer caste”; the single muzzled ones from south of Korhogo, the double-muzzled from the west.

44.Prouteaux, 1918-1919, p. 38. Maesen, 1940, pp. 388 ff., suggests that besides chasing soul-eaters the masks play a “political” role which, although less ostensible, may be their “real” function.

45. Prouteaux, 1918-1919, p. 48. He also points out, p. 51, that some of the older woman, known as sorcerers, have on the contrary a certain connection with a demon mask, whose costume they prepare, and who must ask their permission to enter the village.

46. Prouteaux, 1918-1919, p. 48. Paulme, 1956, p. 43, follows Prouteaux, as does Leuzinger (1960, p. 95, and 1963, p. 76), but the mask illustrated is a kagba rather than a typical firespitter.

47. Prouteaux, 1918-1919, p. 48.

48. Maesen, 1940, p. 391.

49. Maesen, 1962. It must be noted that although Prouteaux and Maesen (at an interval of 25 years) are in entire agreement on the function of these masks, and in fact of “firespitting,” their descriptions of its mechanism differ. Prouteaux evidently did not see sparks issue from the muzzle of the mask, while Maesen did. However, Maesen also says (1940, pg. 238) that the mask were worn on the head like a helmet, with “the wearer seeing through the muzzle.” If the muzzle was at eye height, how was it possible to blow sparks through it?

70 Mask. Central region, Ferkessédougou district, Nafarra fraction [S]. Wood, 34″ long. Collection of Jack V. Wallinga, St. Paul

71 Mask. Central region, Ferkessédougou district, Nafarra fraction [S]. Wood, traces of paint, 34″ long. MPA 64.13. Gift of Mrs. Gertrud A. Mellon

In his 1962 communication Maesen confirms the substantial correctness of his information as published in Philadelphia, 1956 catalogue, and adds: “All the korubla masks and some of the other cult groups I managed to watch on the spot showed a coating of molten resin, if not of burned wood. In 1938-39 it was almost impossible to collect actually used specimens. None of the masks brought back showed traces of the molten resin used in ‘firespitting.’ “However, none of the many masks examined in 1963 at the time of the exhibition had any signs of charring, and only one, a mask probably too small to have been worn (Rubin collection) had anything other than a light painted surface, and its encrustation was not resinous.

50. Maesen, 1940, p. 389; Holas, 1960, pp. 56, 59, and fig. 17; Himmelheber, 1960, p. 103, and fig. 88b where it is called lo mask of the “blacksmith caste” from south of Korhogo—(there also being a horned variety west of Krohogo). Maesen also describes a similar monkey, unknown in the central area but frequent in the west, which is used in a pantomime dance of purely recreative intention.

51. Maesen, 1940, p. 241. Lem, 1948, p. 44, and pl 51.

52. Lem, 1948, p. 45, and pls. 54 and 55.

53. Elisofon and Fagg, 1958, fig. 109.

54. Knops, 1956, p. 159, who, however, does not distinguish between kagba and nassolo.

55. We owe this description to Mr. Bochet’s own commentary, kindly communicated with his drawings.

56. Holas, 1957a, p. 152, who quotes Bochet; and Holas, 1960, pp. 59-60, where his description follows Bochet’s drawings.